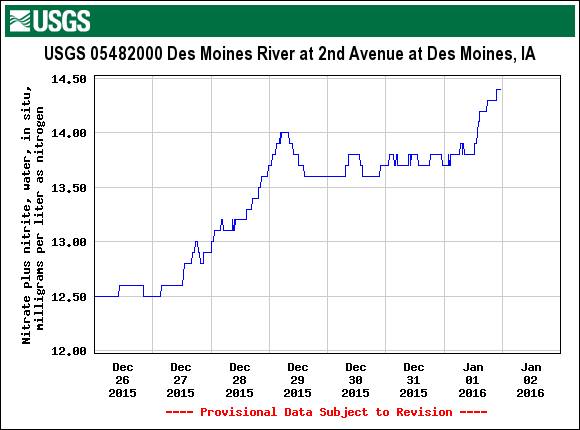

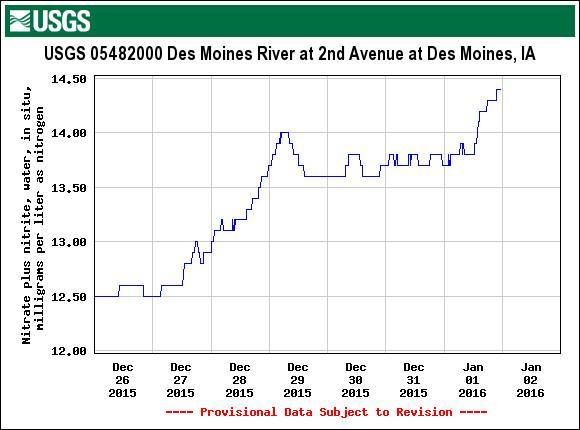

graph of nitrates in the Des Moines River exceeding safe levels, taken by Steven Witmer using data from the U.S. Geological Survey

The Des Moines Water Works announced yesterday that it spent some $1.5 million during 2015 to operate its nitrate removal system “for a record 177 days, eclipsing the previous record of 106 days set in 1999.” The utility provides drinking water to about 500,000 residents of central Iowa, roughly one-sixth of the state’s population. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency considers 10 mg/l the maximum safe level for nitrates in drinking water. The Des Moines Water Works switches the nitrate removal system on when nitrates exceed 9 mg/l in both of its sources, the Raccoon River and the Des Moines River. I enclose below the full press release from the Water Works, as well as charts from the U.S. Geological Survey’s website showing recent nitrate levels in the Raccoon and Des Moines rivers.

Runoff from agricultural land is the primary source of nitrates in Iowa waterways. As David Osterberg wrote yesterday, “so little land in Iowa is devoted to urban uses (lawns or golf courses) that even if urban application rates of Nitrogen and Phosphorous fertilizer were much higher than that on farms, only 2 percent of the pollution from land application of fertilizer comes from lawns and golf courses.” This “nutrient pollution” not only incurs extra costs for providing safe drinking water but also creates toxic algae blooms, which caused a record number of beach advisory warnings during the summer of 2015.

Last January, the Des Moines Water Works filed a lawsuit against drainage districts in northwest Iowa’s Sac, Calhoun and Buena Vista Counties. Drake University Law Professor Neil Hamilton wrote an excellent backgrounder on this unprecedented litigation: Sixteen Things to Know About the Des Moines Water Works Proposed Lawsuit. In a guest column for the Des Moines Register last May, Hamilton debunked the “strenuous effort” to convince Iowans that “the lawsuit is unfair and unhelpful.”

Governor Terry Branstad has depicted the lawsuit as a sign that “Des Moines has declared war on rural Iowa” and repeatedly criticized the Water Works last year. Iowa Secretary of Agriculture Bill Northey claims the water utility “has attempted to stand in the way of these collaborative efforts” to reduce nutrient pollution. A front group funded by the Iowa Farm Bureau and other agribusiness interests and led by Cedar Rapids Mayor Ron Corbett, among others, has also tried to turn public opinion against the lawsuit. In recent weeks, that group with the Orwellian name of Iowa Partnership for Clean Water has been running television commercials seeking to demonize Water Works CEO Bill Stowe.

Northey, Corbett, and Lieutenant Governor Kim Reynolds may soon become bitter rivals for the 2018 GOP nomination for governor. But those three will stand together opposing any mandatory regulations to reduce agricultural runoff. All support Iowa’s voluntary nutrient reduction strategy, shaped substantially by Big Ag and lacking numeric criteria strongly recommended by the U.S. EPA.

William Petroski and Brianne Pfannenstiel report in today’s Des Moines Register that Branstad “is exploring a legislative proposal that would provide money for water quality projects by using projected revenue growth from an existing statewide sales tax for schools.” Apparently “superintendents have been getting called to the state Capitol to discuss the proposal” with Branstad and Reynolds. Fortunately, that cynical attempt to pit clean water against school funding appears to have zero chance of becoming law. Of the ten state lawmakers or representatives of education or environmental advocacy groups quoted by Petroski and Pfannenstiel, none endorsed the half-baked idea. Their reactions ranged from noncommittal to negative. Speaking to Rod Boshart of the Cedar Rapids Gazette, Iowa Senate Majority Leader Mike Gronstal said of a possible Branstad proposal on water quality funding, “We certainly would be willing to look at that but we’re not going to cannibalize education or the basic social safety net so that he can put a fig leaf on his record on the environment.”

UPDATE: Erin Murphy reported more details about Branstad’s proposal: extend the 1 percent sales tax for school infrastructure, dedicate the first $10 million in annual growth to schools and allocate the rest to water programs.

SECOND UPDATE: Added below excerpts from Murphy’s report for the Cedar Rapids Gazette on Branstad’s plan. I’m disappointed to see U.S. Secretary of Agriculture Tom Vilsack endorse this ill-conceived proposal. Of course we “need to work on [water quality] now,” but why does the money have to come out of school funds? Remember, the Branstad administration is already pushing a corporate tax break that will cost public school districts millions of dollars a year for infrastructure on top of tens of millions of dollars in lost state revenue.

THIRD UPDATE: Branstad told reporters today he does not believe there is support in the legislature to raise the sales tax. Under a constitutional amendment adopted in 2010, 3/8 of a cent of the next Iowa sales tax increase would flow into the natural resources trust fund. He also indicated that he would not support extending the penny sales tax for school infrastructure beyond 2029, when it is scheduled to expire, without lawmakers agreeing to divert some of the funding to water programs. According to incoming Iowa House Speaker Linda Upmeyer, “House Republicans have been divided on whether to extend the school infrastructure sales tax beyond 2029.”

Des Moines Water Works news release, January 4:

DES MOINES WATER WORKS’ 2015 DENITRIFICATION RECORD

Des Moines Water Works ended 2015 operating its nitrate removal facility for a record 177 days, eclipsing the previous record of 106 days set in 1999. Operational costs for denitrification in 2015 total $1,500,000.

Des Moines Water Works meets or exceeds regulatory requirements for drinking water established by the United States Environmental Protection Agency, including delivering drinking water to our 500,000 Central Iowa customers with nitrate concentrations below 10 mg/L or parts per million. However, the costs and risks in doing so are increasingly high as Iowa’s surface waters demonstrate dangers levels of pollutants.

The increase in river nitrate levels is attributable to upstream agricultural land uses, with the largest contribution made by application of fertilizer to row crops, intensified by unregulated discharge of nitrate into the rivers through artificial subsurface drainage systems.

“Iowa’s political leadership, with influence from industrial agriculture and commodity groups, continue to deny Iowa’s water quality crisis,” said Bill Stowe, CEO and General Manager, Des Moines Water Works. “Defending the status quo, avoiding regulation of any form, and offering the illusion of progress and collaboration, places the public health of our water consumers at the mercy of upstream agriculture and continues to cost our customers millions of dollars.”

Des Moines Water Works seeks relief against upstream polluters and agricultural accountability for passing production costs downstream and endangering drinking water sources. In addition, Des Moines Water Works is actively planning for capital investments of $80 million, a cost funded by ratepayers, for new denitrification technology in order to remove nitrate and continue to provide safe drinking water to a growing central Iowa.

Graph of nitrate levels in the Des Moines River, shared by Steven Witmer, taken from the U.S. Geological Survey’s website.

UPDATE: From Erin Murphy’s January 5 report, “Branstad plan: Shift some school tax revenue to water quality programs.”

Under Branstad’s plan, which requires legislative approval, the school infrastructure sales tax — which is set to expire in 2029 — would be extended to 2049, and annual revenue increases would be divided: the first $10 million in new revenue each year would go to schools, and the remaining would go to water quality programs.

Branstad’s office estimates the proposal would generate $7.5 million for water quality programs in the first year and $4.7 billion over the next 32 years. […]

[Former Democratic Governor and U.S. Agriculture Secretary Tom] Vilsack sat next to Branstad at Tuesday’s meeting and called the governor’s plan a “solid framework” that promptly addresses an issue that needs immediate attention. […]

“There is a limited period of time to work on this water quality issue. The reality is we need to work on it now,” Vilsack said.

Branstad’s plan was met with hesitation from Democratic Senate Majority Leader Mike Gronstal, who criticized the plan for using future school infrastructure funding to pay for water quality programs.

“Sacrificing that (future school infrastructure funding) for the sake of another priority, for water, I don’t think makes a lot of sense,” Gronstal said. “It is a solution, an effort that undercuts local schools.”

Murphy later updated his story with more reaction:

Iowa State Education Association President Tammy Wawro echoed Gronstal’s sentiment that Branstad’s plan equates to “robbing Peter to pay Paul.” Wawro expressed exasperation that Branstad’s plan includes reducing future school infrastructure funding after years of what she and many schools think has been inadequate state funding for school districts.

“I’m really at a loss, to be honest, that we’re even having a discussion about this,” Wawro said. “The fact that we’re even having a conversation about this, taking even part of the pie meant for kids to take care of another important priority, it’s just very disturbing right now for us.”

Sioux City School District Superintendent Paul Gausman appeared at Tuesday’s news conference at the Capitol and expressed support for the governor’s proposal. Gausman said he approves the plan because it ensures the school infrastructure sales tax will be extended, which would allow schools to use long-term loans to fund infrastructure projects.

“The way I look at this is in 2029 that number goes to zero,” Gausman said. “With this extension, that number continues for us, with $10 million in annual growth.”

JANUARY 6 UPDATE: Jason Noble and Brianne Pfannenstiel reported more reaction to the governor’s plan.

“I was actually hopeful after last summer’s vetoes of spending for education that the governor had run out of ideas on how to undercut our local schools,” Gronstal said in a press conference ahead of Branstad’s announcement.

At press conference in the Capitol that followed, Branstad appeared with former Iowa Democratic governor and current U.S. Secretary of Agriculture Tom Vilsack and outlined the plan while flanked by several education and agricultural leaders from around the state.

Among them was Kirk Leeds, who cited his experiences as the executive director of the Iowa Soybean Association and president of the Boone School Board in his endorsement of the plan.

“I think it’s a win-win,” Leeds said. “Education gains additional dollars, additional ability to make long-term infrastructure investment, and farmers will continue to partner with the USDA and the state to make investments to improve water quality.” […]

Schools would be guaranteed all the SAVE funds they currently receive, plus an additional $10 million every year. Additional revenues beyond that $10 million would be shifted to water quality projects as the state’s tax base grows.

An estimate compiled by the Iowa Department of Revenue projects Branstad’s plan would divert $4.7 billion in tax receipts to water quality initiatives over a 32-year period, while maintaining almost $21 billion for schools. The projections show funding for water quality initiatives would begin at $7.4 million in 2017 and rise steadily, ultimately hitting $374.6 million in 2049. School infrastructure funding, meanwhile, would increase from $468 million in 2017 to $778 million in 2049.

Branstad cast the proposal as an innovative approach that would raise revenue for critical needs without raising taxes on Iowans.

“This is the biggest and boldest initiative probably I’ve ever put together in all my years as governor,” he said.

No Comments