Dave Swenson

It is an article of faith that Iowa’s businesses are tax-burdened. Ask anyone. Farmers believe property taxes are unfair, shopkeepers bemoan the burdens of eking out a profit while still obliged to contribute to the public purse, and manufacturers uniformly lament the erosions in interstate and international competitiveness they say are caused by Iowa’s archaic system of taxes. It all makes for good rhetoric, but in the main it is not true: Iowa taxes on businesses are, like Iowans, just about average, if not a little better. And Iowa’s manufacturers enjoy a particularly privileged position compared to other commerce in the state and to other manufacturers nationally.

All of that notwithstanding, the Iowa Department of Revenue recently held hearings to eliminate, using administrative rule-making powers, a set of sales taxes typically owed by manufacturing firms. Mike Ralston, President of the Iowa Association of Business and Industry, wrote in the Des Moines Register that Iowa’s manufacturers “expect and desire to pay all the taxes they owe.” But he noted manufacturers ought to not owe these particular taxes because they amounted to double taxation, a dubious claim at best.

Writing in Bleeding Heartland, Jon Muller informed us this would be incrementally more costly to the state’s fiscal accounts over time and that the need and justification for tax relief in this very narrow area of business activity was somewhat sketchy. And the sage Peter Fisher of the Iowa Policy Project, responding in the Des Moines Register to this legislative end-run, weighed in arguing that this “tax break is not an incentive; it is a gift to business.”

It is an easy task to evaluate Iowa’s overall situation regarding the full complement of production-related taxes that oblige Iowa businesses. The U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis provides annual estimates of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) for state industrial categories. GDP at the state level is composed of all compensation to employees, gross operational surplus (i.e., returns to owners and investors), and business taxes on production and imports (mostly use, sales, excise, and property taxes). By dividing the taxes portion of GDP by the total, we get a fix on the relative total tax bite burdening Iowa’s manufacturing industry in the aggregate.

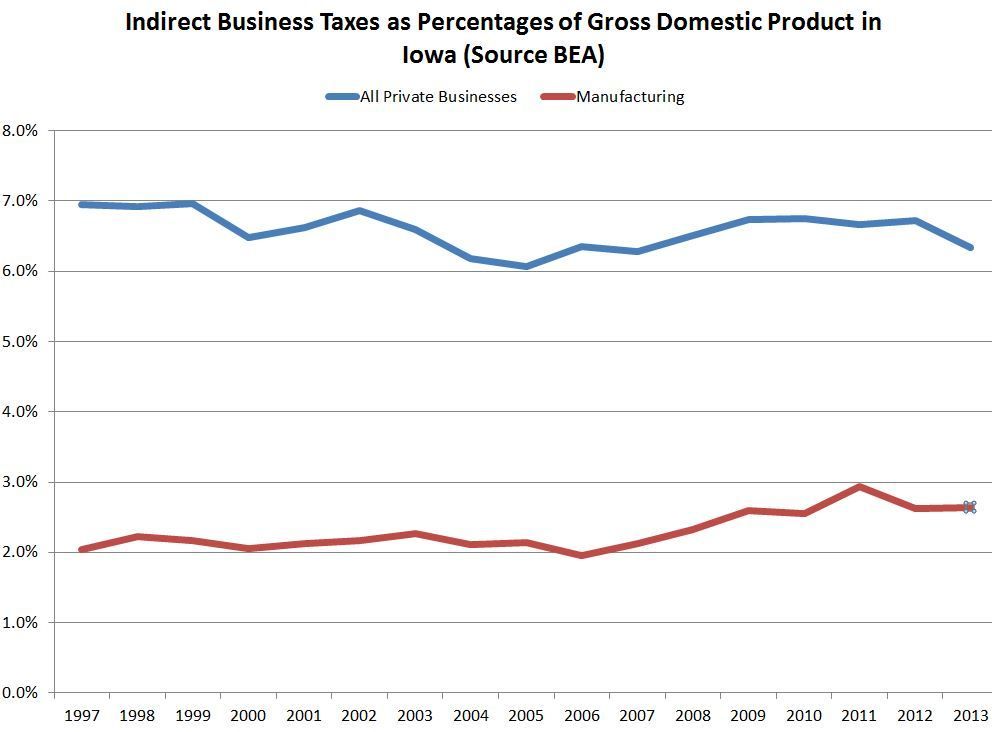

The first graphic below demonstrates Iowa manufacturers’ tax burden as a fraction of GDP as compared to all private businesses in Iowa.

In 2013, the average Iowa private producer paid about 6.2 percent of the total worth of GDP in all production related taxes; Iowa’s manufacturers’ taxes averaged only 2.6 percent – less than half the tax burden of the typical Iowa industry.

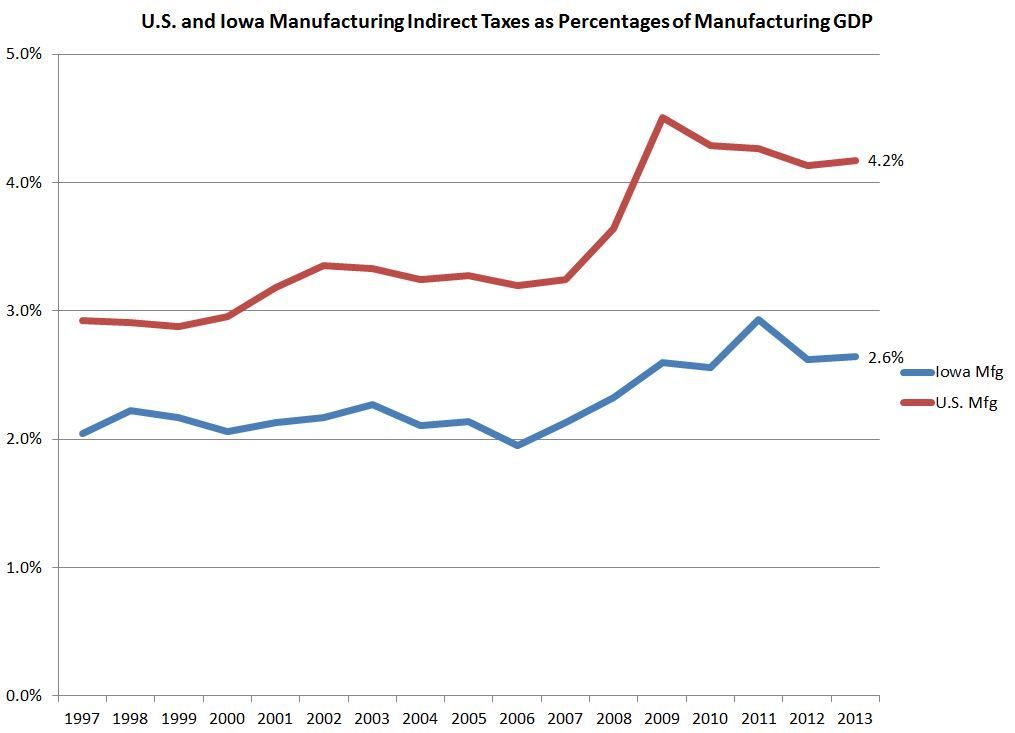

Even though manufacturers’ tax bite is much lower than the average Iowa non-manufacturing industry, it is still prudent to compare Iowa’s situation with the U.S. After all, if Iowa compares unfavorably with the rest of the U.S., one could make the argument that its competitive position is undermined irrespective of its extremely favorable position within the state.

Using the same GDP data components, the next graph compares Iowa manufacturing to U.S. manufacturing. In 2013, the U.S. average rate of production taxes as a fraction of GDP was 4.2 percent; in Iowa it was 2.6 percent, or nearly 40 percent less than the national average. There is absolutely no evidence that Iowa’s national competitive position has eroded because of its production-related taxes. (note, the sharp rise in production tax percentages in the U.S. and in Iowa from 2007 to 2011 was because of the Great Recession: the denominator shrank while other taxes, like property taxes, remained comparatively constant.)

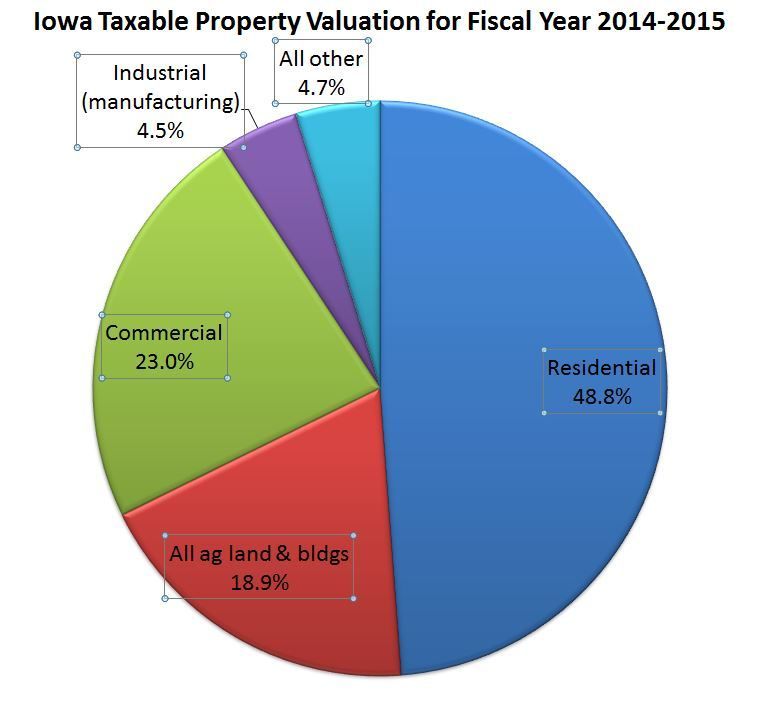

As both Jon Muller and Peter Fisher pointed out in their articles, Iowa’s manufacturers have benefitted over the years by very favorable tax exclusions, most notably the elimination of manufacturing machinery and equipment from the property tax rolls in the 1990s. In so doing, Iowa manufacturers, who in fact directly account for 11 percent of total jobs in Iowa and a full 18.3 percent of the state’s GDP, only pay property taxes on 4.5 percent of the state’s taxable property valuation.

Finally, given Iowa’s national manufacturing prominence, one should compare Iowa’s GDP tax bite with all other states in the U.S. to ascertain for certain Iowa’s national place on this important topic of industrial competitiveness. That ranking is in the following table. Iowa is 37th nationally in manufacturing taxes using this interstate measure, which should not be a surprise given what has been presented thus far.

Iowa manufacturers enjoy an advantaged position in Iowa regarding their production-related tax obligations as compared to other Iowa industries. That is simply unarguable. Taxes on the GDP wealth they generate for workers, owners and investors, and for governments are much lower than that for the whole of Iowa’s private sector, they are much lower than that borne by national manufacturers, and they are much lower than the national average among the states.

Iowa manufacturers also enjoy a range of other lucrative tax-relieving benefits. In fiscal 2014 a full 30 percent of the state’s manufacturing property tax base was within a tax increment financing district, which means that the taxes that they owed were likely rebated back to them or were used to underwrite the development of public infrastructure that benefits them disproportionately.

Iowa manufacturers (as do other businesses) also enjoy lucrative state income tax credits if they expand or, in recent years, merely modernize. And local governments have been trained to ante up as well in these instances. Last, but not least, Iowa manufacturers are the primary beneficiaries of research activity tax credits, which totaled nearly 57 million in 2014. And these credits were totally refundable even if the firm, like is the case for many of Iowa’s manufacturers, don’t owe that much in state taxes.

So, while industry representatives like Mr. Ralston will tell you, and it is true, that Iowa manufacturing jobs are some of the best jobs pay-wise one can get in Iowa, it is also true that there are, notwithstanding our recovery, a full 10 percent fewer manufacturing jobs in Iowa than there were in 2001. And that long slide in manufacturing jobs is a persistent trend that has little if anything to do with the state’s current levels of taxation of manufacturing.

3 Comments

More Like This, Please

This is nuts and bolts government analysis of the sort we too seldom get to read.

One of my history teachers at UI long ago said the essence of government was in the tax and spending decisions. Prior to that I had always thought government was about civil rights and race relations and war and peace. Nowadays we could be forgiven for thinking government is all about religion or abortion or immigration.

Since I now know better, I am always looking for tax and spending explanations.

Can you tell us where gambling taxes fit in? How much do we depend on lotteries and casinos to fund our government? Is that revenue in lieu of taxes we used to collect or is it gravy on top of other taxes?

iowavoter Mon 26 Oct 7:35 PM

Gambling Taxes Detail

Gaming revenues are a relatively small (but not inconsequential) portion of Iowa’s overall revenues. Based on the estimates from the October 2015 meeting of the State’s revenue estimating conference (REC), lottery revenues for the current fiscal year are estimated to total $72.4 million, while revenue from racing and gaming facilities are estimated to total $277.9 million – a combined $350.3 million.

It is notable that racing and gaming revenues are not technically general fund revenues – they are dedicated to other funds. However, if we combine estimated FY2016 general fund revenues with racing and gaming revenues, they would total $7,097.6 million; which would mean that lottery plus racing and gaming revenue would be 4.9 percent of this total.

There was no direct ‘enact the lottery/racing and gaming laws and we’ll reduce x taxes’ (as there were in some states – or at least an implicit promise to dedicate the revenues to a specific source, which was frequently education) so it is hard to make the case either way. In fact, racing and gaming revenues have generally been dedicated for infrastructure, which was not a bad idea (the theory being in early years that the revenue stream from racing and gaming was not well established so better to use for one-time projects as opposed to ongoing operations).

arby58 Tue 27 Oct 7:13 AM

Thanks, Arby58

for answering my question.

iowavoter Wed 28 Oct 6:35 PM