A U.S. District Court judge has ruled unconstitutional an Idaho law that criminalized lying to obtain employment at an agricultural facility or making unauthorized audio and video recordings at such facilities. Will Potter, one of the plaintiffs challenging the “ag gag” law, has been covering the case at the Green is the New Red blog. Judge Lyn Winmill’s ruling (pdf) found that the Idaho law’s provisions violated both “the Free Speech Clause of the First Amendment and the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment” of the U.S. Constitution.

The Iowa House and Senate approved and Governor Terry Branstad signed our state’s version of the “ag gag” law in 2012. It was the first of its kind in the country.

Although Iowa’s law differed from the Idaho statute in some ways, several parts of yesterday’s federal court ruling would appear to apply equally to Iowa’s law. After the jump I’ve enclosed the relevant language from both state laws and excerpts from Judge Winmill’s ruling.

Agriculture industry groups started pushing for laws to protect against whistleblowers after undercover videos shot by animal rights activists exposed some appalling practices. In early 2011, the Republican-controlled Iowa House approved the first version of an “ag gag” bill. Nine Democrats and 57 Republicans voted for the legislation, which made it a crime to obtain access to farms on false pretenses or to possess and distribute unauthorized audio or video recordings from farms.

You didn’t need to be a lawyer to recognize potential First Amendment problems with such a bill. It went nowhere in the Democratic-controlled Iowa Senate in 2011.

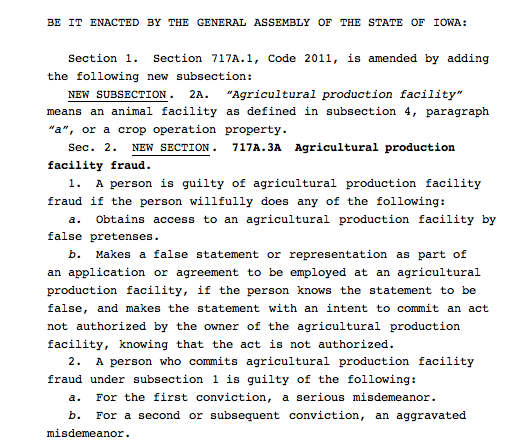

Big Ag’s friends in the upper chamber revived the bill the following year. Because the Iowa Attorney General’s Office warned that the legislation could be challenged on First Amendment grounds, supporters took out the language about audio and video recordings. Here’s the key excerpt from the final version of House File 589 from 2012. (I enclose it as a screenshot because the old permalink takes you to the unrelated House File 589 introduced during this year’s legislative session.) UPDATE: Here is the link to the full text of that bill.

In February 2012, sixteen Democrats joined all 24 Republicans to approve the amended ag gag bill in the Iowa Senate. The same day, twelve Democrats joined 57 Republicans to pass the bill in the Iowa House. Bleeding Heartland covered those votes here, for anyone interested to know which Democrats jumped on that bandwagon. At the time, State Senator Matt McCoy described the legislation as “incredibly bad public policy for a nonexistent problem that is being worked across the country by big ag that doesn’t want to play by the rules and has had it their way for a long time.”

Idaho lawmakers weren’t as cautious as their Iowa counterparts. They created a new crime called “interference with agricultural production,” which occurs if a person knowingly:

(a) is not employed by an agricultural production facility and enters an agricultural production facility by force, threat, misrepresentation or trespass;

(b) obtains records of an agricultural production facility by force, threat, misrepresentation or trespass;

(c) obtains employment with an agricultural production facility by force, threat, or misrepresentation with the intent to cause economic or other injury to the facility’s operations . . .

(d) Enters an agricultural production facility that is not open to the public and, without the facility owner’s express consent or pursuant to judicial process or statutory authorization, makes audio or video recordings of the conduct of an agricultural production facility’s operations; or

(e) Intentionally causes physical damage or injury to the agricultural production facility’s operations, livestock, crops, personnel, equipment, buildings or premises.

Idaho adopted the language on audio and video recordings despite obvious First Amendment problems. But points (a) and (c) from the Idaho law resemble language in Iowa Code.

U.S. District Court Judge Winmill granted summary judgment to the plaintiffs on First Amendment and Fourteenth Amendment grounds. Many pages of the ruling address the unconstitutional limits on free speech imposed by the ban on making audio and video recordings at agricultural facilities.

Other portions could easily apply to Iowa’s ag gag law, though. On page 7, Judge Winmill describes how Upton Sinclair misrepresented himself in order to gain employment at a meat-packing facility. Working there provided the material for Sinclair’s influential novel The Jungle.

Today, however, Upton Sinclair’s conduct would expose him to criminal prosecution under § 18-7042.

The State [of Idaho] responds that § 18-7042 is not designed to suppress speech critical of certain agricultural operations but instead is intended to protect private property and the privacy of agricultural facility owners. But, as the story of Upton Sinclair illustrates, an agricultural facility’s operations that affect food and worker safety are not exclusively a private matter. Food and worker safety are matters of public concern. Moreover, laws against trespass, fraud, theft, and defamation already exist. These types of laws serve the property and privacy interests the State professes to protect through the passage of § 18- 7042, but without infringing on free speech rights.

Pages 8 through 11 of the decision discuss case law on what forms of false speech are protected under the First Amendment and the difference between those false statements and others that are not protected (such as perjury or defamation). The judge notes,

[T]he most likely harm that would stem from an undercover investigator using deception to gain access to an agricultural facility would arise, say, from the publication of a story about the facility, and not the misrepresentations made to gain access to the facility. Id. In this scenario, there would not be compensable harm for fraud or defamation based on the lies the investigator told to gain access to the facility. See, e.g., Food Lion, Inc. v. Capital Cities/ABC, Inc., 194 F.3d 505, 512-513 (4th Cir. 1999). And harm caused by the publication of [a] true story is not the type of direct material harm that Alvarez contemplates. Hustler Magazine, Inc. v. Falwell, 485 U.S. 46, 42 (1988).

It is true that the Alvarez plurality at one point said those false claims “made to . . . secure moneys or other valuable considerations, say offers of employment,” are not protected. 132 S. Ct. at 2547. But the State has submitted no evidence that the lies an undercover investigator might tell or the omissions an investigator might make to gain access or secure employment at an agricultural production facility are made for the purpose of material gain. Rather, undercover investigators tell such lies in order to find evidence of animal abuse and expose any abuse or other bad practices the investigator discovers. Thus, the proposed misrepresentations at issue here do not fit the Alvarez plurality’s description of unprotected lies because they would not be used to gain a material advantage. Id. (holding Stolen Valor Act violated First Amendment because it prohibited lies “without regard to whether the lie was made for the purpose of material gain”). Indeed, the lies used to facilitate undercover investigations actually advance core First Amendment values by exposing misconduct to the public eye and facilitating dialogue on issues of considerable public interest. This type of politically-salient speech is precisely the type of speech the First Amendment was designed to protect.

Although Iowa’s law did not criminalize audio and video recordings at agriculture facilities, its ban on misrepresenting oneself to gain access to such a business could still be an unconstitutional content-based restriction on speech. From page 18 of yesterday’s ruling:

In fact, § 18-7042 discriminates not only based on content but also on viewpoint. The natural effect of both the audiovisual recording prohibition and the misrepresentation provision found in § 18-7042(1)(c) is to burden speech critical of the animal-agriculture industry. Id. at 24. The recording prohibition gives agricultural facility owners veto power, allowing owners to decide what can and cannot be recorded, effectively turning them into state-backed censors able to silence unfavorable speech about their facilities. I.C. § 18- 7042(1)(d). Section 18-7042(1)(c) effects the same result by criminalizing only a subset of misrepresentations made to gain employment with an agricultural production facility with the intent to cause economic or other injury. This means, under § 18-7042(1)(c), a job applicant who lies to secure employment with the goal of praising the agricultural production facility will skate unpunished. But a job applicant who fails to mention his affiliation with an animal welfare group with the intent of exposing abusive or unsafe conditions at the facility will face the full force of the law. MDO re Motion to Dismiss, p. 24.

On page 19, the judge goes on to say:

The State’s interest in protecting personal privacy and private property is certainly an important interest. But in the First Amendment sense, these are not compelling interests in the context presented here. Alvarez, 132 S. Ct. at 2549 (noting that the Government’s interest in protecting integrity of Medal of Honor was beyond question, but finding this interest did not satisfy the Government’s heavy burden when seeking to regulate protected speech). Content-based restrictions on speech have been permitted “only when confined to the few ‘historic and traditional categories [of expression] long familiar to the bar,” like obscenity, “fighting words,” defamation, and child pornography. Alvarez, 132 S.Ct. at 2544. The journalistic and whistleblower speech that § 18-7042 aims to suppress certainly does not fall in those categories.

Nonetheless, the State would have the property and privacy interests of agricultural production facilities supersede all other interests. But food production is a heavily regulated industry. And agricultural production facilities already must suffer numerous intrusions on their privacy and property because of the extensive regulations that govern food production and the treatment of animals. Given the public’s interest in the safety of the food supply, worker safety, and the humane treatment of animals, it would contravene strong First Amendment values to say the State has a compelling interest in affording

these heavily regulated facilities extra protection from public scrutiny.

Beginning on page 23, Judge Winmill addresses the equal protection claims under the Fourteenth Amendment. These paragraphs from page 24 suggest that a federal court might find Iowa’s law unconstitutional on the same grounds.

The State contends that the purpose of § 18-7042 is to protect the private property of agricultural facility owners by guarding against such dangers as trespass, conversion, and fraud. But the State fails to explain why already existing laws against trespass, conversion, and fraud do not already serve this purpose. The existence of these laws “necessarily casts considerable doubt upon the proposition that [§ 18-7042] could have rationally been intended to prevent those very same abuses.” Moreno, 413 U.S. at 536- 37.

Likewise, the State fails to provide a legitimate explanation for why agricultural production facilities deserve more protection from these crimes than other private businesses. The State argues that agricultural production facilities deserve more protection because agriculture plays such a central role in Idaho’s economy and culture and because animal production facilities are more often targets of undercover investigations. The State’s logic is perverse-in essence the State says that (1) powerful industries deserve more government protection than smaller industries, and (2) the more attention and criticism an industry draws, the more the government should protect that industry from negative publicity or other harms. Protecting the private interests of a powerful industry, which produces the public’s food supply, against public scrutiny is not a legitimate

government interest.

And from the following page:

As the Supreme Court has repeatedly said, “a bare congressional desire to harm a politically unpopular group cannot constitute a legitimate governmental interest if equal protection of the laws is to mean anything.” Moreno, 413 U.S. at 534. As a result, a purpose to discriminate and silence animal welfare groups in an effort to protect a powerful industry cannot justify the passage of § 18-7042. Id. at 534-35.

I would guess it’s only a matter of time before Iowa’s ag gag law is struck down.

UPDATE: I am seeking comment from Governor Terry Branstad on this court ruling and whether Iowa’s lawmakers should amend or rescind the Iowa Code provisions on “agricultural production facility fraud.”

SECOND UPDATE: Branstad’s communications director Jimmy Centers responded, “House File 589 passed with bipartisan support and under the advice and counsel of the Attorney General’s office. The governor has not had the opportunity to review the ruling from the federal court in Idaho and, as such, does not have a comment on the case.”

I decided to post the details on the 2012 votes for House File 589. All 24 Iowa Senate Republicans voted for the bill, as did 57 of the 60 Iowa House Republicans (the other three were absent that day; I am not aware of any who opposed the bill).

The following 16 Senate Democrats also voted to criminalize “agricultural production facility fraud.” Unless otherwise indicated, they still serve in the upper chamber.

Daryl Beall (defeated in November 2014)

Dennis Black (retired in 2014)

Tom Courtney

Dick Dearden

Gene Fraise (retired in 2012)

Mike Gronstal

Tom Hancock (retired in 2012)

Wally Horn

Jack Kibbie (retired in 2012)

Amanda Ragan

Tom Rielly (retired in 2012)

Brian Schoenjahn

Joe Seng

Steve Sodders

Mary Jo Wilhelm

Other than Gronstal (Council Bluffs), Horn (part of Cedar Rapids), and Seng (part of Davenport), most of the Democrats who supported the ag gag bill represented districts containing rural areas as well as cities.

These ten Senate Democrats voted against House File 589 in 2012. All represented largely urban or suburban districts:

Joe Bolkcom

Jeff Danielson

Bill Dotzler

Bob Dvorsky

Jack Hatch (retired in 2014 to run for governor)

Rob Hogg

Pam Jochum

Liz Mathis

Matt McCoy

Herman Quirmbach

Twelve of the 40 Iowa House Democrats voted for the final version of the ag gag bill. Unless otherwise indicated, they still serve in the lower chamber:

Deborah Berry

Mary Gaskill

Curt Hanson

Dan Kelley

Kevin McCarthy (was the House minority leader at the time; resigned his seat mid-term in 2013)

Helen Miller

Dan Muhlbauer (defeated in 2014)

Brian Quirk (resigned soon after winning re-election in 2012)

Roger Thomas (retired in 2014)

Andrew Wenthe (retired in 2012)

Nate Willems (left House seat to run unsuccessfully for Iowa Senate in 2012)

John Wittneben (defeated in 2012)

Other than Berry, Miller, and McCarthy, most of the above represented districts including rural areas.

The following 28 Iowa House Democrats voted against the ag gag bill. Other than Swaim, most represented largely urban or suburban districts:

Ako Abdul-Samad

Dennis Cohoon

Ruth Ann Gaines

Chris Hall

Lisa Heddens

Bruce Hunter

Chuck Isenhart

Dave Jacoby

Anesa Kajtazovic (retired in 2014 to run for Congress)

Jerry Kearns

Bob Kressig

Vicki Lensing

Jim Lykam

Mary Mascher

Pat Murphy (retired in 2014 to run for Congress)

Jo Oldson

Rick Olson

Tyler Olson

Janet Petersen (did not seek re-election to House in 2012, was elected to Iowa Senate)

Kirsten Running-Marquardt

Mark Smith

Sharon Steckman

Kurt Swaim (retired in 2012)

Todd Taylor

Phyllis Thede

Beth Wessel-Kroeschell

Cindy Winckler

Mary Wolfe