Iowa Republican lawmakers aren’t sticklers for tradition. They have used their trifecta to destroy a collective bargaining process that stood for more than four decades, and to overhaul a nearly 60-year-old judicial selection system on a partisan basis.

Iowa Senate Republicans have shattered norms in other ways. In 2021, they stopped participating in budget subcommittee meetings that had been a routine part of legislative work since at least the 1970s. Last year, they kicked all journalists off the chamber’s press bench, which had been designated for the news media for more than a century.

Senate Appropriations Committee members hit a new low for transparency last week. Led by chair Tim Kraayenbrink, Republicans advanced seven spending bills with blank spaces where dollar amounts and staffing numbers would normally be listed.

The unprecedented maneuver ensured that advocates, journalists, and Democratic senators will have no time to thoroughly scrutinize GOP spending plans before eventual votes on the Senate floor. Nor will members of the public have a chance to weigh in on how state funds will be spent during fiscal year 2024, which begins on July 1.

Bleeding Heartland was unable to find any former Iowa legislator, lobbyist, or staffer who could remember anything resembling this year’s Senate budget process.

“HOW A DEMOCRATIC PROCESS IS SUPPOSED TO WORK”

Randy Bauer staffed the Iowa Senate Appropriations Committee for Democrats from 1986 to 1998, then served as Governor Tom Vilsack’s budget director for six and a half years.

In an April 7 email, Bauer described the budget process Iowa lawmakers used for many years. Joint House and Senate Appropriations subcommittees covering different areas of the state budget met regularly, usually three times a week for about two months.

At those meetings, lawmakers reviewed the governor’s budget proposal and heard from state agency directors and key staff about their budget requests and the governor’s recommendations.

Sometime after the governor released a budget (which typically happened during the first week of the legislative session), the appropriations subcommittees agreed on spending targets for each area, Bauer explained.

The process of setting joint targets existed regardless of control of the chambers – joint targets were set when Democrats controlled both chambers, when Republicans controlled both chambers and also in some years where there was divided control.

At the end of this open process, the budget subcommittees prepared their subcommittee appropriations bill, which included actual appropriations, FTE (full time equivalent) caps for the departments, and any legislative intent or statutory changes needed to implement the bills. Those bills then went to the House or Senate Appropriations Committee where changes to the bill and ultimate passage was done, again in open meetings.

That is a transparent process that includes both the general public, interest groups, and minority party members as well as the majority. It is how a democratic process is supposed to work.

Kraayenbrink’s approach could hardly be more different.

THE FIRST STEPS AWAY FROM NORMAL BUDGETING

After Republicans gained a trifecta in 2017, the budget subcommittees continued to operate normally for several years. Although House and Senate leaders didn’t always agree on joint targets early in the session, they didn’t hide their overall spending plans. For instance, in late February 2019, Senate Republicans published fiscal year 2020 spending targets for the various budget areas—Administration and Regulation, Agriculture and Natural Resources, Economic Development, Education, Health and Human Services, Justice Systems, and Transportation and Infrastructure.

When Iowa Senate Republicans ended the budget subcommittee tradition for the 2021 session, leaders depicted the change as a COVID-19 safety protocol: “Joint budget subcommittees will no longer meet. The House and Senate will schedule budget subs separately. Senate budget subcommittees are expected to be on an ‘on-call’ basis.”

Those “on-call” meetings never occurred. Senate leaders didn’t publish their spending targets until late March.

State Senator Joe Bolkcom, the ranking Democrat on Appropriations at the time, wrote in an April 2021 newsletter that avoiding the budget subcommittees left senators from both parties “without the key information on the needs and work of state agencies.”

Moreover, this is the dedicated space and time for members to ask questions about spending decisions or raise concerns about the work of the Executive Branch agencies. This is especially detrimental for new members who know very little about the budget and appropriation process. The budget subcommittees are where members learn about the budget and how the appropriation process works. I am sure Senate Majority Leader [Jack] Whitver loves to have all the power over these decisions as he keeps his new members and Democrats in the dark.

Senate leaders assigned members to Appropriations subcommittees in 2022, but again, Kraayenbrink and the various subcommittee chairs did not convene any public meetings. Nor did Republicans participate in budget subcommittees involving House members and state agency directors or staff.

Senate Republicans avoided most of the budget subcommittees held on the House side this year, but the Senate’s Health and Human Services budget subcommittee convened once in January to hear a presentation about the governor’s recommendations.

In addition, the senators in charge of the Justice Systems and Economic Development budget subcommittees did hold a few old-style meetings during the 2023 session. Notably, Julian Garrett (Justice Systems chair) and Mark Lofgren (Economic Development) have each served in the legislature for a decade or more, including time in the House prior to winning seats in the upper chamber. Perhaps that experience helped them see the value of meetings where key staff or gubernatorial appointees answer questions in public view.

The Appropriations chair had no interest in following traditional budget practices.

“EXPERTS AT WHAT I’D CALL THREE-CARD MONTE”

Kraayenbrink scheduled Appropriations Committee meetings on April 3 and 4 to consider seven bills he had introduced on March 29. In theory, that gave senators, lobbyists, and regular Iowans a few days to become familiar with the contents before the committee considered the legislation. But those were blank budget bills, so no one would have any idea whether senators planned to spend more, less, or the same as last year for any part of the state government’s work.

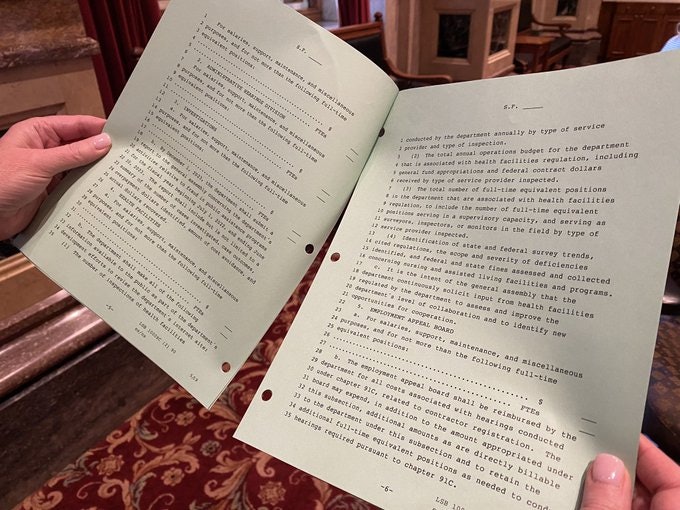

Links to Kraayenbrink’s bills are available here. Democratic State Senator Sarah Trone Garriott posted this view of one proposal on her social media.

Most of the time, Iowa lawmakers consider bills in subcommittee sometime before a full committee hearing, in case amendments need to be drawn up to address feedback from lobbyists or members of the public. As Bauer explained above, that used to be a typical practice for budget bills.

The way Kraayenbrink orchestrated last week’s meetings, the entire Appropriations panel considered the bills in a “subcommittee of the whole,” then moved immediately to full committee approval. Republicans were unable to answer Democrats’ questions about spending targets for each broad budget area, let alone for specific agencies.

Throughout the April 3 and 4 meetings, Kraayenbrink and his GOP colleagues acted as if there were nothing unusual about this bonkers process. Here’s a clip from the subcommittee’s consideration of Senate Study Bill 1209, the Administration and Regulation budget (the full videos are available here).

Kraayenbrink invited public comments (naturally, there weren’t any), then opened the floor to senator comments. State Senator Claire Celsi, the ranking Democrat for this subcommittee, observed, “Probably the reason there’s no comment from the public is because there’s no numbers in our budgets. It’s kind of hard to comment on stuff that has blanks in it.”

As the committee continued to discuss Senate Study Bill 1209, Democratic State Senator Janet Petersen, the ranking member for the full Appropriations panel, tried to ask about various agency plans. But staff were either not present or (in the case of the Department of Administrative Services) didn’t know the answers.

That pattern repeated as the committee took up other blank budget bills. Democrats weren’t able to find out plans for state employees: How many would be needed to run various programs? Where would staff be reduced, and would that happen through attrition or layoffs?

Several Democrats on the committee argued the public should have a chance to weigh in once numbers and staffing details are available. (Subcommittee hearings are typically the only chance for Iowans to speak directly to legislators about pending bills.) Kraayenbrink brushed off those concerns.

Celsi challenged State Senator Dave Rowley, the Admin and Regulation subcommittee chair, on why he had refused her request to schedule subcommittee meetings. He asserted that the information senators received from the government agencies “is available to all of us.” Rowley added that since he had met with staff and several department heads, “At no point were Iowans’ voices cut out, or anyone, we’ve been working through this process. And we will get that opportunity to debate on the floor as well.”

Celsi countered, “That’s simply not true. When we don’t have a joint meeting with the House, like we used to, the public really is in the dark. They’re not invited to your private meetings with department heads. Not only does the public not get to know anything, but the senators don’t either.” (Rowley may genuinely not understand, since he was first elected to the legislature after Senate Republicans ended the budget subcommittee tradition.)

When the full committee considered the Admin and Regulation bill a short while later, Celsi said it was “ridiculous” to waste the senators’ time, and the public’s, on blank budget bills.

State Senator Bill Dotzler, the ranking Democrat on the Economic Development budget subcommittee, sought to pin Kraayenbrink down on whether any of the bills would be brought back to committee with spending numbers and revised policy language. Or was the plan to present an amendment on the Senate floor, with no meaningful public participation?

Kraayenbrink said the goal was to come up with numbers House and Senate Republicans could agree on. He said Lofgren would take some of Dotzler’s feedback to negotiations with the House on the economic development budget. Senate Republicans would then substitute or amend the bill on the floor “and get out of here in a timely manner.”

Dotzler commented that Republicans “appear to be experts at what I’d call three-card Monte.” He likened the process to a “shell game,” becoming increasingly animated as he explained how budgeting used to work. “We’ve gotta get back to allowing the public to have access to the same stuff that we have access to. Not in the backrooms, but in a public opportunity for them to ask real questions.” Dotzler added that department staff need to come to the committee meetings. “This is a real sham.”

He predicted that after Senate Republicans reveal their spending plans, Democratic staff will “be up half the night” trying to figure it out, so senators can understand what they are voting on and offer amendments.

Dotzler’s frustration rose during the Appropriations Committee’s April 4 meeting, as senators discussed the health and human services budget. That is traditionally one of the longest and most complex bills, involving roughly $2 billion in spending. Dotzler noted that the bill covers a “mind-boggling” range of issues.

“I do not understand why we aren’t holding meetings,” not only for the minority party, “but for your own party to understand the nuances of the Department of Human Services.” Addressing Kraayenbrink directly, Dotzler said, “Your members need to be educated and hear the stuff that goes on. You’ve got a new team! You have a new team! And you’re not always going to be the chair. And why wouldn’t you want to educate your members that eventually will take over this committee?”

Of the 34 current Republican state senators, sixteen were first elected in 2020 or later, so have no direct experience with how the Iowa Senate handled budgeting for generations.

Though senators bring many backgrounds to the table, Dotzler went on, “very few of us have worked in this arena. And shame on us that we don’t take this opportunity” to help members understand “what the hell’s going on” in human services.

Raising his voice, Dotzler said he prays the legislature will change its approach to budgeting. “Because that’s why we’re here! It’s the most important thing a legislator can do, is put a budget together that reflects the needs and takes care of the public. And how do you do that, if you do it in a vacuum?”

Kraayenbrink appeared unfazed and responded dismissively. He thanked Dotzler “for your educational experience,” and jokingly warned he may have to move him to another part of the long committee room table.

WHY MOVE BLANK BUDGET BILLS?

It’s not unusual for an Iowa legislative committee to vote out a bill with the understanding that it will be amended on the House or Senate floor. But a budget bill with no details on spending is new territory. Why not hold off until Senate Republicans have something concrete to consider?

Kraayenbrink offered two explanations during and after the April 3 meeting. Neither was credible.

First, he said it was taking some time to incorporate the recently approved state government reorganization plan, which eliminated some agencies, merged others, and moved lots of functions into different departments.

That would have been a good reason not to rush through the governor’s realignment bill. If lawmakers had more thoroughly considered the impact of various elements, they could have adopted a reorganization plan in 2024 without disrupting this year’s budget process. Everyone has known all along that the goal was to finish the legislature’s work by late April.

In any event, Dotzler challenged this pretext, noting that the blank budget bills contained some boilerplate language from last year, which is no longer accurate following the reorganization.

The Appropriations chair also suggested his committee’s action would push House Republicans to start work on spending bills. But according to the Des Moines Register’s Iowa Politics newsletter on April 6, Kraayenbrink “was not aware of the House budget targets released the week before.” (Republicans in the lower chamber are seeking to spend about $90 million more than the governor has proposed for fiscal year 2024; the Senate majority is sticking with the governor’s overall target.)

It’s hard to fathom how the Senate’s top appropriator could be that out of touch with what’s happening on the House side. And Celsi, Dotzler, and others expressed skepticism that advancing blank budget bills would motivate Republicans in the other chamber to work faster.

The scenario Dotzler posited seems to be the most plausible explanation. Senate Republicans don’t want to leave time for a thorough analysis of their spending plans. Once they cut a deal with the House, they will ram budget bills through as strike-after amendments during floor debate.

To paraphrase Bauer, that’s the opposite of “how a democratic process is supposed to work.”

Top image: Iowa Senate Appropriations Committee chair Tim Kraayenbrink (left) and Republican State Senator Dan Zumbach, during an April 3 meeting. Screenshot from official legislative video.

1 Comment

Transparency

I asked my House representative, Henry Stone, about a bill that presented in the House concerning the January 6th ‘protesters’ and their treatment. Stone replied that he doesn’t know what bills are presented in the Senate because he is in the House. I guess that the Republicans don’t get. together to talk about their priorities.

bodacious Mon 10 Apr 9:10 AM