Fifth in a series interpreting the results of Iowa’s 2022 state and federal elections.

Iowa’s final unresolved race from 2022 wrapped up on December 7 when Republican Luana Stoltenberg was declared the winner in House district 81. She received 5,073 votes (50.05 percent) to 5,062 votes (49.95 percent) for Democrat Craig Cooper. Stoltenberg led by 29 votes on election night in the district, which covers part of Davenport. But the Democrat pulled ahead by six votes once Scott County officials tabulated hundreds of overlooked absentee ballots.

It’s rare for a recount in an Iowa legislative race to alter the vote totals by more than a dozen. It’s even more rare for a recount to produce fewer overall votes for each candidate. Yet as Sarah Watson noted in her story for the Quad-City Times, the three-member recount board’s final “totals showed 31 fewer votes for Cooper and 14 fewer votes for Stoltenberg.”

Cooper conceded the race but expressed “grave concerns” about the inconsistent ballot counts in a December 7 Facebook post.

It’s clear that something went very wrong with the processing of absentee ballots in Iowa’s third largest county. The problems warrant further investigation to prevent anything like this from happening again.

RECOUNTS RARELY PRODUCE SIGNIFICANT VOTE CHANGES

Iowa’s voting system, using paper ballots and optical scan machines, produces extremely accurate results. In the fourteen years I’ve closely followed state legislative races, recounts have never before reversed an outcome. It’s common for a recount of 10,000 to 20,000 ballots to change candidates’ vote totals by zero, one, or two votes. The 2020 recount in one high-turnout Iowa Senate race turned up three extra votes out of around 46,000 cast.

How would a recount find additional votes? Sometimes ballots are not properly fed through a scanner, or are not readable by the machine. For instance, if a voter marked an X next to a candidate’s name, instead of filling in the oval, the scanner may record that as an “undervote” (where the voter did not select any option). But humans on a recount board will discern the voter’s intent.

By the same token, machines do not count “overvotes,” where the voter has marked more than one line for the same race. But a small fraction of those ballots could have discernible voter intent, if the voter filled in the oval next to a candidate and wrote the same person’s name on the write-in line.

Occasionally, an Iowa legislative recount will result in tossing out some small number of votes initially tabulated for one contender. But I can’t recall any race where a legislative candidate lost more than a handful of votes.

ONE 2022 RECOUNT WAS NOT LIKE THE OTHERS

Out of six Iowa House races that went to recounts this year, five fit the usual pattern:

- Democrat Josh Turek led Republican Sarah Abdouch by 3,404 votes to 3,397 in House district 20. After the recount, he was declared the winner by 3,403 votes to 3,397.

- Democrat Heather Matson led Republican Garrett Gobble by 6,991 votes to 6,968 in House district 42. Gobble’s representative halted the recount part-way through the process, because none of the precinct totals had changed.

- Democrat Chuck Isenhart led Republican Jennifer Smith by 6,161 votes to 6,066 in House district 72. Each candidate gained a few ballots during the recount; Isenhart’s final winning margin was 6,164 to 6,070.

- Democrat Sharon Steckman led Republican Doug Campbell by 6,328 votes to 5,589 in House district 59. The recount didn’t change Campbell’s vote total but added one ballot for Steckman, producing a final margin of 6,329 to 5,589.

- Democrat Elizabeth Wilson led Republican Susie Weinacht by 7,296 votes to 6,991 in House district 73. The recount reduced Wilson’s winning margin by five votes: 7,297 to 6,997.

Scott County’s roller coaster ride was quite different. Shortly after the November election, several county-wide tabulations kept finding different totals for absentee ballots. Auditor Kerri Tompkins didn’t adequately explain why around 470 absentee ballots (or perhaps 488) were not counted initially, or why the first administrative recount produced a 19-ballot discrepancy. Even the “final” numbers released on November 18, which Secretary of State Paul Pate declared to be accurate, did not match expectations for absentee ballot totals.

Speaking to Ed Tibbetts last month, Tompkins speculated that someone in the absentee room may have set aside a stack of uncounted ballots, thinking they had already been counted. However, video footage did not reveal evidence of that kind of mistake. Tompkins told county supervisors there may have been human or machine errors.

In the House district 81 race, election-night totals showed Stoltenberg ahead by 5,062 votes to 5,033. When all absentee ballots were supposedly accounted for, Cooper appeared to be leading by 5,093 votes to 5,087.

The recount board (a Democrat selected by Cooper, a Republican representing Stoltenberg, and a Democrat agreed on by the other two members) spent several days going through ballots last week. They should have finished their work by December 2, but came up with “47 fewer absentee ballots cast in the race than the county auditor’s tallies,” Watson reported. (The election-day totals matched perfectly for every precinct.)

After diving back into the absentee ballots this week, a Democratic member of the recount board turned up two additional votes for Stoltenberg. They never did figure out what happened to 45 absentee ballots that (according to the county auditor’s tally) contained 31 more votes for Cooper and fourteen more votes for Stoltenberg. They submitted a final count of 5,073 to 5,062, which will be certified.

Cooper told the Quad-City Times this week, “There were 31 votes that just simply disappeared. […] I have no idea whether the ballots weren’t run or whether the ballots never existed.” He wrote on Facebook, “I accept the results and the incredible efforts of the recount board, but I still have grave concerns about the Republican Scott County auditor office that could not arrive at the same number of ballots cast twice.”

University of Iowa law professor Derek Muller, who served on a Johnson County recount board in 2020, noted that mistakes may happen when a batch of ballots is run through a machine twice (or not at all) on an initial count. That could explain some extra votes for candidates in House district 81. But remember: Cooper’s six-vote lead wasn’t based on the first pass through Scott County’s absentee ballots. That was after the county auditor’s staff had gone through the absentee ballots at least three times.

Weinacht’s representative on the House district 73 recount board blasted what he called the “incompetence and inexperience” of the Linn County auditor’s office, due to a discrepancy of nine absentee ballots between the election-night total and what the recount board found in that race. But it’s common for results to change slightly between election night and the final tabulation. Linn County Auditor Joel Miller has been forthcoming about the glitches that held up the November 8 absentee ballot tabulations in the county containing the Cedar Rapids metro.

In contrast, Scott County Auditor Tompkins told the Quad-City Times this week that she remains “100% confident” in her office’s recount practices.

PROSPECTS FOR IMPROVING IOWA RECOUNTS UNCLEAR

Staff for the Iowa Secretary of State’s office did not respond to Bleeding Heartland’s inquiries about whether Pate still vouches for the accuracy of the Scott County administrative recount, or plans to investigate the anomalies there. Pate publicly criticized the election night mishaps in Linn County, where the auditor (a Democrat) was the party’s 2022 nominee for secretary of state. Will he give Tompkins a pass because she’s a Republican?

Tompkins told Tibbetts her office would submit a report on the errors to the state, but she also said “she’s not sure if a definitive answer will be found.” According to that report, “it is still unclear if the original discrepancy was due to the machines or human error.” It did not address the discrepancy between the recount board’s tally and the administrative recount finding.

Stoltenberg told the Quad-City Times the recount process needs “more defined lines and boundaries and a few more defined rules so candidates know where they stand.”

Although Republicans have changed Iowa’s election laws many times since they gained full control of state government in 2017, they have not meaningfully reformed the rules on recounts. The extremely close 2020 election in Iowa’s second Congressional district—Mariannette Miller-Meeks was certified the winner by six votes out of around 394,000 cast—exposed many problems with how state law governs the process. For example, the law provides no uniformity of procedures across precincts or counties. Recount boards are capped at three members even in large counties where more than 100,000 ballots may need to be reviewed.

Outgoing Senate State Government Committee chair Roby Smith and House State Government Committee chair Bobby Kaufmann introduced a bill in early 2022 that would address part of the code on recounts. It made it through committee in both chambers but never received a House or Senate floor vote.

Muller sharply criticized the proposal in comments to Bleeding Heartland in February, while that bill was pending.

This bill is written as if no one talked to anyone who conducted the recount. It doesn’t adequately give resources for counting in a timely fashion, because hand counts take dramatically longer and have a much higher risk of errors and error corrections. Some of the micromanaging principles it codifies in the hand count make no sense, such as requiring overvotes and undervotes to be put into one pile when hand counting.

It doesn’t improve the method of a recount, such as permitting a machine-assisted tally to target overvotes and undervotes.

It doesn’t improve coordination across counties by strengthening the role of the Secretary of the State and simplifying the process to request a recount when dealing with a recount that crosses county lines.

It doesn’t narrow the opportunity for recounts to only viable challengers, or to contests within a narrow band of results, which were not in issue in 2020 but are weaknesses in the present law.

In short, it cleans up a few small things and leaves a lot of areas untouched where there ought to be broad consensus among election officials and candidates alike.

Smith is leaving the legislature at the end of the year (he was just elected state treasurer), and Kaufmann will lead the House Ways & Means Committee next year.

Bleeding Heartland sought comment last month from the incoming leaders of the Iowa House and Senate State Government committees on whether they will pursue any changes to state law on recounts during the 2023 legislative session. Neither State Representative Jane Bloomingdale nor State Senator Jason Schultz replied to the messages.

UPDATE: Tompkins told the Des Moines Register that the recount board initially conducted a machine count, which showed Cooper ahead but with the numbers changed “a little bit.” They then reviewed ballots by hand.

“The duty rests on the recount board to determine what information they are going to place in their report,” Tompkins said. “So they can choose which results they want to go with.”

Different counting methods should not result in a discrepancy of dozens of ballots. Someone should go through Scott County’s absentee ballots again to find out how many were marked for a candidate in House district 81.

That seems unlikely. Kevin Hall, spokesperson for the Iowa Secretary of State’s office, told the Des Moines Register in a written statement, “The bipartisan recount board members, which include two Democrats and one Republican, have publicly stated they are confident in the results of their recount and we thank them for their efforts.”

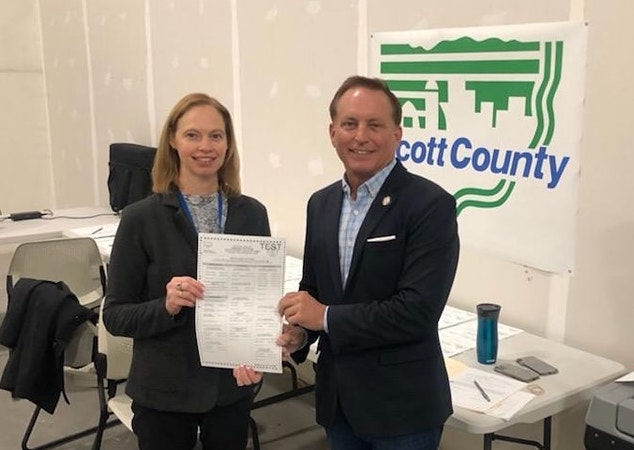

Top photo: Scott County Auditor Kerri Tompkins (left) and Iowa Secretary of State Paul Pate pose during an October 2022 public testing of vote tabulators. Photo originally posted on Pate’s official Facebook page on October 26.